ABOUT OUR EXPERTS

ECDA Fellow and Director (Strategic Initiatives), Little Seeds Preschool

ECDA Fellow and Deputy Head, Preschools, Star Learners Group

Early childhood (EC) leaders face a multitude of challenges every day, from mentoring a new generation of educators to managing parents’ expectations. To better support these EC leaders, ECDA Fellows Mrs Cara Wong and Ms Stacey Toh have been trying to help them develop clarity and courage in decision-making through conversations and exchanging of practical strategies.

“We had many conversations about decision paralysis among leaders,” explains Ms Toh. “There’s also the avoidance of difficult conversations. As nurturing individuals who hold values like love and kindness, EC professionals often feel the need to maintain harmony and peace. But we need clarity as well, to understand difficult situations.”

“Deciding to have difficult conversations takes courage,” adds Mrs Wong. “Those who do so recognise the reality of the situation and take action, regardless of the outcome.”

GAINING CLARITY WITH THE CYNEFIN FRAMEWORK

As a sense-making tool, Dave Snowden’s Cynefin framework helps simplify and demystify complexity through categorisation. It asks users to assign factors or aspects in a situation to one of four key quadrants:

- Complex, requiring a probe-sense-respond approach

- Complicated, requiring a sense-analyse-respond approach

- Chaotic, requiring an act-sense-respond approach

- Clear (or Simple), requiring a sense-categorise-respond approach

The Cynefin framework helps demystify the complexities faced in the EC-related decisions you need to make every day.

The Cynefin framework helps demystify the complexities faced in the EC-related decisions you need to make every day.

Mrs Wong cites an example where, due to an educator’s error, a child is accidentally fed an allergen and rushed to the hospital. In this situation, the preschool leader is beset by multiple priorities. She needs to check on the child, inform the parents and write an incident report, all while grappling with emotions such as panic, worry and fear.

“It’s important to recognise that the situation is complex — not because you don’t know what to do, but because it involves various stakeholders with possible escalation at many points, as well as different perspectives and emotions,” says Mrs Wong. “Instead of worrying about these uncontrollable factors, focus on what you can control and allow that to inform your decision about what to do first.”

Using the Cynefin framework, the centre leader in the same example considers what she knows of the situation to prioritise tasks and choose appropriate actions. When a task — such as deciding whether the child’s absent form teacher or the Chinese teacher, who was present, should call the parents — is assigned to the Complex quadrant, the quadrant’s approach provides clarity into next steps.

“There’s no correct answer for this task, so try probing based on what you know,” says Mrs Wong. “Next, sense how to go from there, and then develop your response. The goal is to quickly de-escalate the situation, bringing it from Complex to Complicated and down to Clear. Don’t let it get to Chaos.”

FINDING STRENGTH IN COURAGEOUS LEADERSHIP

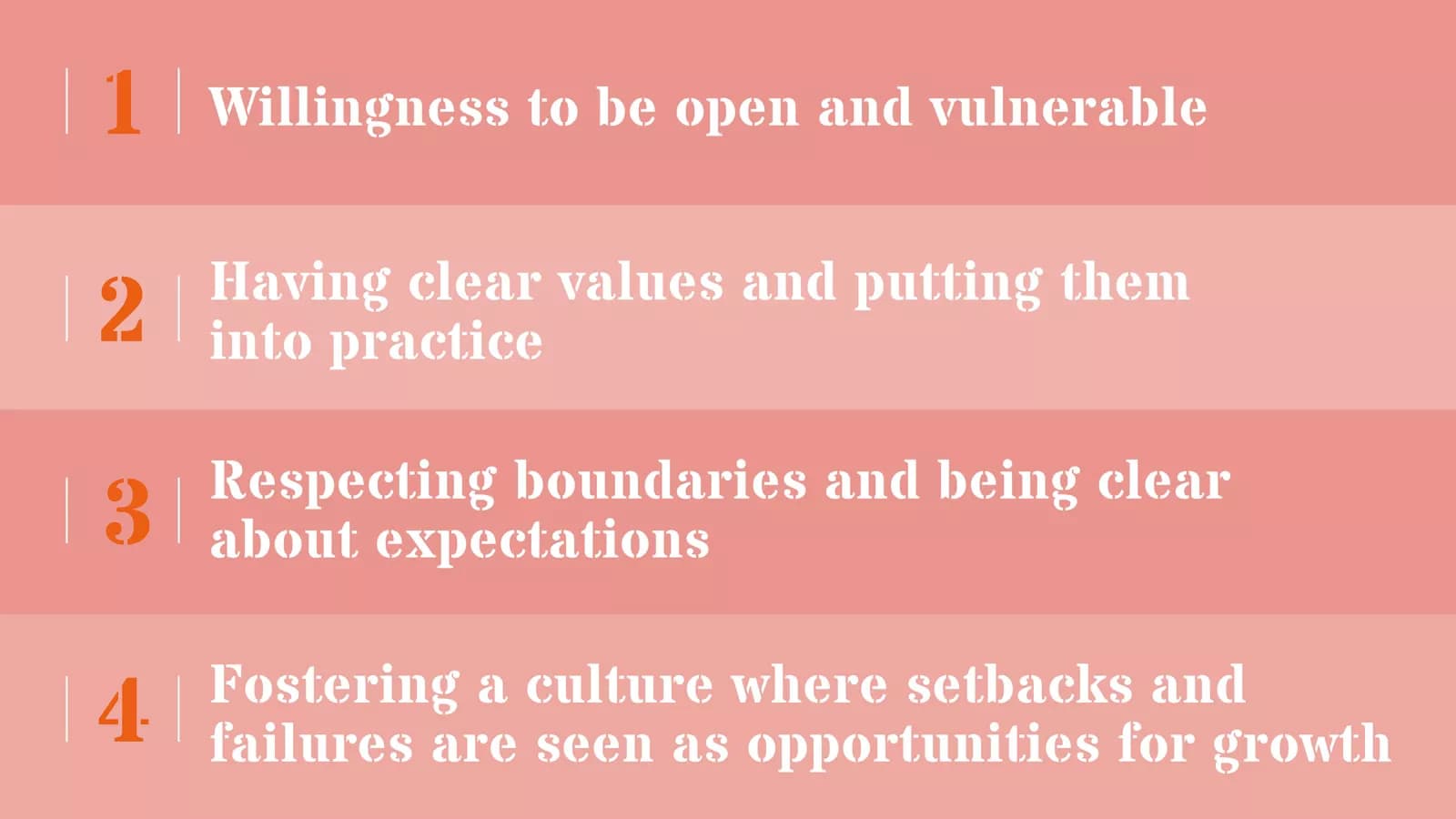

Brené Brown’s Courageous Leadership model is built on four pillars:

Continuing the allergy incident example, Ms Toh explains that it takes courage for the preschool leader to inform the upset parents of the situation without hiding the truth.

Continuing the allergy incident example, Ms Toh explains that it takes courage for the preschool leader to inform the upset parents of the situation without hiding the truth.

“You have to open yourself up to questioning and backlash that affects you emotionally,” says Ms Toh. “After that’s settled, you have to comfort the crying teacher, but also let her know that she’s done something wrong and there will be consequences.”

She adds that the leader must then cooperate with the human resources department on the investigation, continue de-escalating the situation with the child’s parents, take ownership of the oversight, and reflect on the centre’s standard operating protocols to identify weaknesses. “The Courageous Leadership model comes in at all these different junctures.”

STAYING ANCHORED AMID DAILY PRESSURES

To use these decision-making tools effectively, self-reflection — knowing your personal values and analysing the why and how of your actions — is key.

Mrs Wong suggests that EC leaders picture themselves as a ship at anchor, battered on all sides by the tide: “The tide may be constantly moving around you — like when there’s a new teacher, an angry parent, or the fear that your centre will close down. Self-reflection determines the bedrock of who you are and enables you to stay true to yourself. Without it, you’ll lose your anchor and become something you’re not, or capsize and burn out.”

Both ECDA Fellows share tips on how to practise self-reflection:

- Take time on a weekly or daily basis. As little as 10 minutes a day works.

- Be with yourself. Shut out all distractions.

- Revisit your pains and successes of the day or week.

- Notice patterns. If something routinely challenges you, ask yourself why.

- Engage in peer dialogue. Ask one or two trusted confidants to act as voices of reason.

“There’s a lot of noise in EC leadership, and it can be a struggle to concentrate on your inner voice,” notes Ms Toh. “Through intentional self-reflection, you can identify blind spots, gain clarity into what to prioritise, align actions with your values, and pluck up the courage to manage these challenges.”