ABOUT OUR EXPERT

Dr Grob-Zakhary is the founder and CEO of Education.org, a non-profit foundation that partners with governments and education system leaders to improve learning outcomes by distilling complex evidence into actionable guidance. With a background in medicine and neuroscience, she moved into global education driven by a passion to bridge the gap between knowledge and practice. She is an established speaker and author, having written numerous works on early childhood education, including BABYBOOST: Fifty Things About Babies & Toddlers Every Parent Should Know.

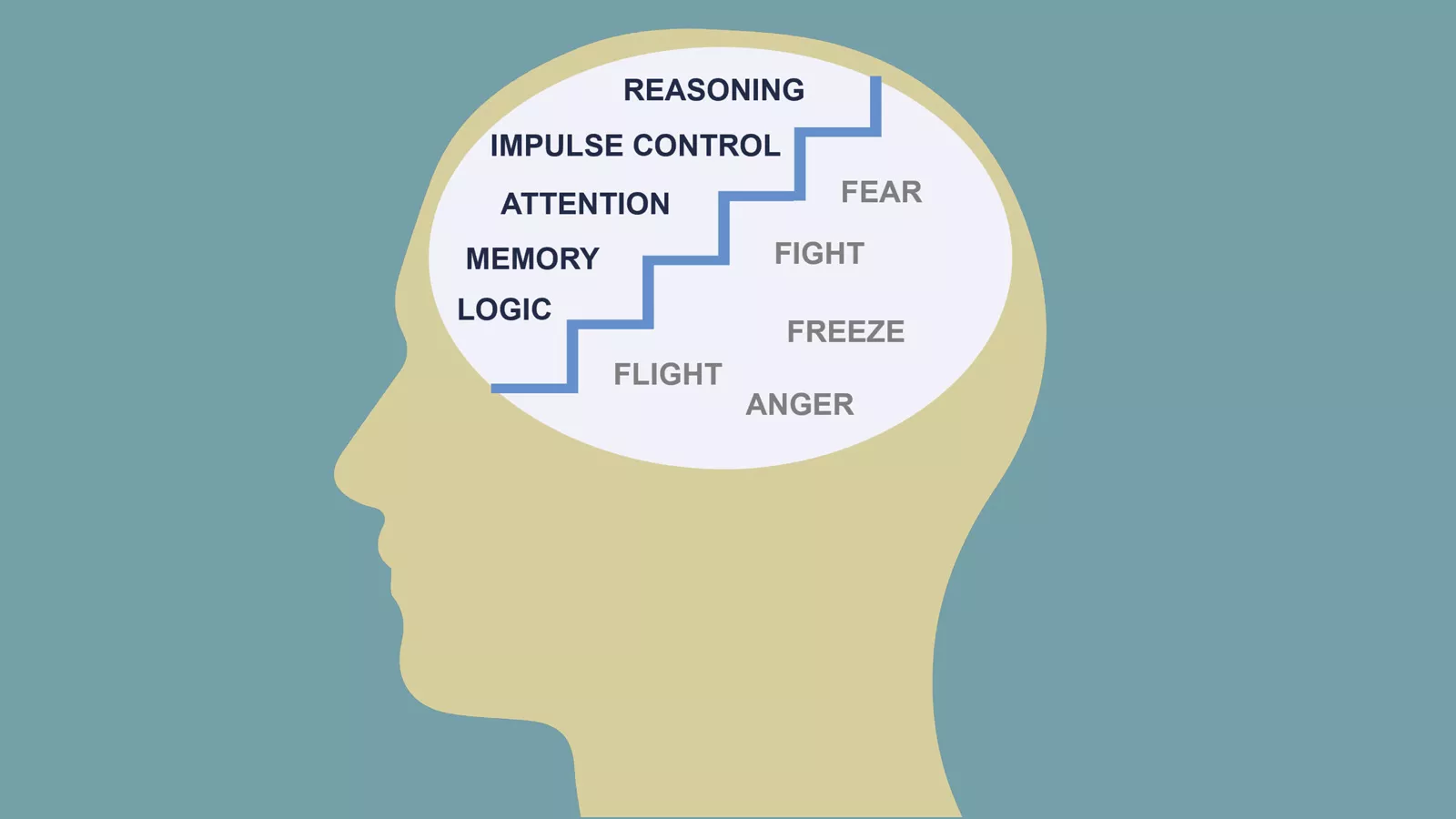

When we talk about a child’s ‘upstairs brain’, we mean the part that helps them think clearly, solve problems and manage their feelings. It’s where focus, memory and self-control live. But the upstairs brain is delicate. When a child feels safe and comforted — through a calm word, a steady routine or a caring touch — it stays switched on. That’s when they can listen, learn and make good choices.

When stress hits, the brain flips into ‘survival mode’. The upstairs brain goes quiet, and the ‘downstairs brain’ takes over — fuelling big emotions such as anger or fear, and quick reactions like fight, flight or freeze.

Gentle, consistent responses from adults can bring the upstairs brain back online. Small acts, such as naming an emotion or keeping routines steady, help children reconnect and feel safe to learn again.

The brain is like a house with two floors: ‘downstairs’ for basic needs and emotions, and ‘upstairs’ for thinking and planning. It is important to build the ‘stairs’ to connect or balance both parts for better emotional regulation and decision-making.

The brain is like a house with two floors: ‘downstairs’ for basic needs and emotions, and ‘upstairs’ for thinking and planning. It is important to build the ‘stairs’ to connect or balance both parts for better emotional regulation and decision-making.

RESPOND WITH EMPATHY

In the early years, children’s brains are still wiring up the pathways that shape how they handle stress, focus and connect with others. Understanding the distinction between the upstairs and downstairs brain helps adults see misbehaviour not as wilful disobedience, but as a signal that a child is seeking safety and reassurance from a trusted caregiver. Rather than reacting with frustration, we can respond with a calm voice and steady presence, helping the child re-engage their upstairs brain and begin to regulate their emotions.

For children with anxiety, trauma or neurodivergent needs (e.g. attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or autism), this understanding is even more important. Their brains may be especially sensitive to change, sensory input or stress, which means their upstairs brain can go offline more quickly. What appears to be misbehaviour may actually be sensory overload or a need for predictability. With the right response, such as familiar routines or simply giving them space to regroup, adults can help them feel safe and supported again.

PARENTS AS THE ‘EMOTIONAL CLIMATE’ OF THE HOME

Every household has a ‘climate’ — it can feel calm and sunny, or stormy and unsettled. Parents set the emotional weather of the home. Children tune in to the tone of family life: the way parents speak to them, the way they speak to each other, or how they handle stress.

In the personal environment of the home, children see their parents in unfiltered moments, such as when they are tired, busy or worried. This makes parents’ emotional signals even more powerful. A calm response, predictable routines, or repairing with kindness after a rough exchange can make a child feel safe, supported and ready to learn.

HOW TO DEAL WITH EVERYDAY TRIGGERS

Everyday stressors can quickly pull children into their downstairs brain. What may look like defiance is often just a young brain overwhelmed by emotions. With foresight, adults can reduce these triggers or respond in ways that help children return to calm.

Common home scenarios:

- Running late in the morning: In the rush to get out the door, a child forgets their favourite soft toy and gets upset. Instead of expressing frustration, a parent might say: “I know you love Bunny. Let’s keep a special photo of Bunny in your backpack, so you can feel close even if we forget.”

- Sibling rivalry: A brother grabs the bigger cookie, causing an argument. Resolve it calmly by saying to them, “Let’s make this fair. We’ll break it in half and share.”

- Unexpected guest: A neighbour drops by, interrupting playtime. Rather than forcing immediate politeness, prepare your child: “We’ll pause our game for 10 minutes while I talk with Auntie, then we’ll finish playing together.”

- Loud noises: A vacuum or blender is suddenly used, setting off tears. Parents can warn beforehand: “This machine is noisy, but it’s safe. Let’s cover our ears together.”

- Being yelled at: A child spills juice on the floor. Instead of shouting, model calm problem-solving: “Oops, spills happen. Let’s get a cloth together.”

WORK WITH THE PRESCHOOL

Just as parents set the tone at home, educators fulfil that same role in the classroom. When parents and educators work together to create steady emotional climates, children feel secure and grow more resilient. This gives them confidence to both cope and flourish.

Strategies to consider include:

- Shared routines: If the preschool plays a lullaby during naptime, parents might sing a gentle song before bedtime at home too. Familiar signals help children feel secure.

- Common language: If parents and educators both use the same phrase when a child is upset (e.g. “Let’s take a calm breath”), the child learns one simple, reliable tool they can use anywhere.

Being consistent doesn’t mean being perfect. What matters most is that children can trust the adults around them to respond with steadiness and care. That sense of trust becomes the foundation for their confidence, resilience and love of learning.